Jason, Jimi and Joe

The long, strange legacy of "Hey Joe" fuels Jason Schneider's latest book

This weekend marks the third anniversary of this newsletter. This is my 297th post here since 2022, after switching from a very irregular blog that debuted in October 2006.

Thank you, dear readers, for listening and engaging and enduring my onslaught of opinions.

I’m currently #70 on Substack’s “Rising” chart, whatever that means — but I’m ahead of #76 Jeff Tweedy (who is actually #2 overall, I guess he’s just no longer “rising.”)

[This week’s live music listings are here.]

Have you noticed my new logo? That’s from my old friend and bandmate Nick Craine, whose new book collecting his life’s work as an illustrator is out now. I wrote the intro. I just got my copy in the mail and it’s a work of beauty.

I started this newsletter for myriad reasons, one of which was to promote my books — in a culture and in a country that usually forgets about books a week after they’re published, if they’re lucky enough to get any notice at all. Especially books about Canadian music.

To mark this week’s occasion, I talk to a co-author of my first book: Jason Schneider, who is celebrating a new book of his own, his fifth.

—

Around this time 25 years ago, with our friend Ian A.D. Jack, Schneider and I co-wrote Have Not Been the Same (next September marks the anniversary of its release). Jason was the main instigator of the three, shopping the project to agents and publishers until landing on ECW Press. For that alone I am eternally grateful; without him, I likely would not have had the hustle to write a book in the first place, never mind three.

I’m a huge fan of his book Whispering Pines, a prequel of sorts to our book together; I consider my own Hearts on Fire to be a sequel in a trilogy. Our co-author Ian Jack is still a good friend: he’s been a more active musician than either Jason or me, and is doing far more tangible and immediately valuable work as an elementary school music teacher.

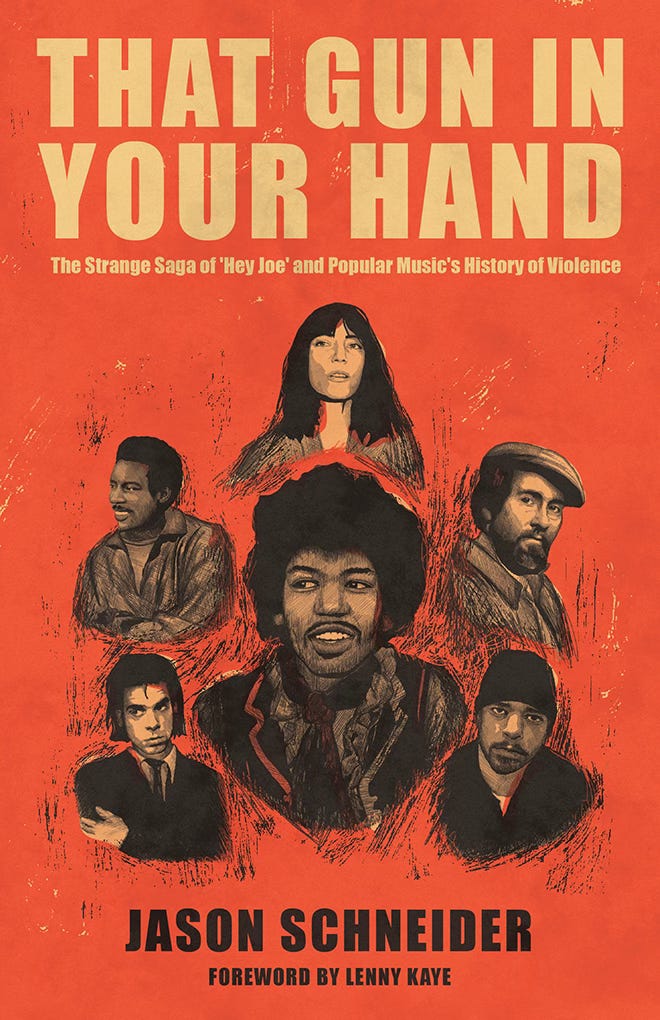

Jason’s new book is called That Gun in Your Hand: The Strange Saga of ‘Hey Joe’ and Popular Music’s History of Violence. It came out on Anvil Press this summer, following his 2022 Art Bergmann biography, The Longest Suicide. In August, it got a full-page review in the Winnipeg Free Press, the last Canadian newspaper that gives a damn about books.

When I first heard about this project, I thought he was nucking futs. A book about one song? And that song is “Hey Joe,” really? Not my favourite Jimi Hendrix song — wouldn’t even make my top 10 — and I’ll confess I’m generally averse to murder ballads.

And yet: I loved this book.

Before reading it, I really had no idea that the song’s provenance was a mystery: written by Billy Roberts, someone who didn’t seem to have any other credits or recordings, and a song that was erroneously credited to others at a time when folk and blues traditions were slow to catch up to modern copyright law.

I also had no idea just how often it was covered, both before and after Jimi Hendrix’s signature version, nor did I realize that an up-tempo arrangement was common for many L.A. garage bands of the mid-’60s, including the Byrds and Love. That’s before you even get into versions by Wilson Pickett, Patti Smith, Nick Cave, Ice T, Charlotte Gainsbourg and, uh, Cher.

Schneider filters it all through an ambitious Greil Marcus-ian lens, roping in social history and biography to help understand what exactly it is about this murderous song that proved to be so enduring: the music follows a circle of fifths, the lyrics are a conversation, the narrator is a bystander to a confession, the culprit’s fate is unknown. Mystery is baked into its measures.

There’s also the fascinating, previously unknown story of two women key to the story: Niela Miller, a Greenwich Village songwriter who was friends with Billy Roberts, and who wrote a song that directly influenced “Hey Joe”; and Linda Keith, who was dating Keith Richards and connected Hendrix with both the song and the manager who made his career.

In a coup of a cosign, Schneider tracked down Lenny Kaye — Patti Smith’s guitarist and curator of the first essential collection of ’60s garage rock, 1972’s Nuggets — who agreed to write the book’s foreword.

It’s the holiday season! I highly recommend this excellent book about a disturbing song for the nerdiest music nerd in your life. Now, let’s get super-nerdy:

Jason Schneider

November 10, 2025

Locale: My living room, before we went to see Robert Plant at Massey Hall. Plant covered “Hey Joe” in 2002.

Why?

Good question.

What I like about this book is that I like things that choose one moment in time or one object to explore a bunch of different things. Is that what drew you to this subject? Did you want to write a book like this for a while and then settle on this song as a prism to do that?

Short answer: yes. I look at it in three different areas.

1) I’ve always been fascinated by Billy Roberts, the mystery surrounding him going back to when I first heard “Hey Joe,” Jimi’s version, and then seeing other versions pop up with different credits. I realized the proper credit is Billy Roberts, and finding any information on him, pre-Internet days, was virtually impossible. He never recorded the song himself, officially. He didn’t seem to make any recordings at all. Nothing about him. It was always in the back of my mind. If I could find this guy’s story, there had to be something to it.

The second path was to use “Hey Joe” as a doorway into an alternate view of ’60s music, because the song was covered so frequently. That’s the question “why”: why was it covered so much?

Do you like the song? Coz if you do, it shouldn’t be a mystery why it was covered so often.

Yeah, I love the song. It is a great song. Even in the realm of “Louie Louie” and “Gloria,” to me, it’s the third part of the garage-rock trinity. It’s much darker than either of those. It’s a narrative story. Why, at the height of the British Invasion, and everything else in popular music at the time, was this song about a guy murdering his girl so popular? That took me into a lot of areas.

Plus the fact that there was a whole question about authorship, different versions of the song being used as sources. That was fascinating to me, to get into the inner workings of how the music industry developed during that time. Looking at its legacy after Jimi died, why did it remain so relevant to so many different genres of music? Those are my three concepts.

And you have a thing for murder ballads.

I do. There’s something in me that connects with that, going back to early blues and country music. In some ways they served the same purpose that true crime podcasts do today.

The obsession with how far someone would take their emotions — emotions that everyone likely has, but thankfully very few take them to these extremes.

The whole notion of crimes of passion. How do you condense that into a three-minute song? The early murder ballads, they were graphic but they weren’t narratives. They were almost like police reports. Like “Little Sadie.” [The song that gave the Sadies their name.]

Is that in third-person?

No, a lot of them are first-person. In “Little Sadie” the crime happens in the first line, and the rest of the song is what happens to the guy: he runs away, gets caught, goes to trial, gets sent to prison. With “Hey Joe,” there is no resolution to the song. What happens to this guy?

Because the song is narrated by a bystander.

Exactly.

You touch on this only briefly in the book, but a song whose popularity has always fascinated me is “Tom Dooley,” which was a huge hit for the Kingston Trio in the late ’50s, three guys who are very clean-cut, white college boys, who sing very pleasantly about a terrible, terrible thing. I’ve never understood the appeal—not of the song, but of that version of that song, at that time in history.

It’s a great question, why that song broke through. That was the era of McCarthyism, either the height or the tail end, and the most prominent voice in folk music then was Pete Seeger. He wasn’t singing murder ballads, but he was at the forefront of bringing this music more exposure and popularity. Maybe “Tom Dooley” just had a catchy melody.

There’s no menace in that version.

Definitely not. Do you know the version Elvis Costello and T-Bone Burnett did?

I don’t.

It was a duo they had called the Coward Brothers, around the time of King of America. Their version is awesome. They do a more uptempo take. It’s definitely a catchy song, once you hear it you can’t forget the hook. [Note: they’ve never recorded it; it appears only on live bootlegs from 1986.]

I knew nothing, obviously, about Billy Roberts. How did you find all these pieces of his life?

One of the first places I went to was this website created by a guy in Europe, which catalogs every known version of “Hey Joe,” which is just insanity. [There are currently 1,800 versions listed.] He’d do the occasional post about Billy Roberts, whatever information he knew. But in the comments section, people would write in and say that they knew him and that he was a good guy, or whatever.

That’s how I managed to connect with [Roberts’s friend and fellow Greenwich Village songwriter] Niela Miller. She is in her eighties, and she’s still alive: she got in touch with me about a month ago. I first interviewed her about five years ago, then we lost touch. I was really thrilled to hear she was still around and knew about the book. She became one of my primary sources. She had amazing information about him.

I followed some more breadcrumbs, manged to find a guy in Washington DC, who could verify that Billy copyrighted the song at the Library of Congress. Then the guy who ended up managing Billy when he made it to San Francisco—he was an amazing source for that period of his life. One thing led to another and the pieces started falling in place.

I loved hearing Niela Miller’s song that morphed into “Hey Joe.” He didn’t rip her off, per see, but you can tell that the two of them were close and that he knew her song, which is also a circle of fifths, but a different melody, and somewhat similar lyrical content.

Yeah, it’s still structured like a conversation. That’s the big similarity, along with the chord progression.

Had you ever heard the song before?

I might have found it on YouTube. Having her tell the story herself was great.

Did anybody else know that lineage? Was she connected with “Hey Joe,” or Roberts, at all before in the public knowledge?

No. Not that I could tell, not until the advent of YouTube. Some label in New York released a bunch of her demos.

Was there any interest in those, though? She never really went beyond Greenwich Village.

No. I’d never heard anything about her up until then.

You say that Roberts did record the song in Vancouver.

In early 1965 he came up to Vancouver to play this coffeehouse called the Ark. There was a guy there who was a budding recording enthusiast, and invited Billy to come over to his place and one of the songs he did was “Hey Joe.”

But that never came out anywhere.

Only on YouTube. This guy’s archive was just discovered only a few years ago.

Was he alive?

No. He opened a professional studio in Vancouver at the end of the ’60s, so he had a treasure trove of stuff, including lots of local Vancouver bands. Whoever was in charge of going through his archives stumbled across this Billy Roberts tape.

He made a couple of other demos that are floating around out there. I found that fascinating: I thought I knew about the Greenwich Village scene, but I didn’t realize how, pre-Dylan, how staunch they all were about the oral folk tradition. We knew this with the story of Bonnie Dobson and “Morning Dew,” but if you wrote an original song, it was a badge of honour for someone else to perform it — no one really cared about copyright.

So it’s unusual that he actually did copyright it in 1962.

Yeah, for that time it was. I couldn’t determine what motivated him to do that, but it was probably just living in Washington and thinking, ‘Well, I’m here, I might as well do it.’

What was the story with [Torontonian] Bonnie Dobson again? She sold her song for beans, or someone just took it?

She didn’t bother to copyright it until Tim Rose recorded it.

Tim Rose who also shows up in this book, appropriating “Hey Joe.”

Yes. The infamous Tim Rose.

I’m trying to remember from the book: did he credit Roberts?

No, he didn’t. He claimed ownership of it. He recorded it in 1966, so there were already versions of it around. He couldn’t legally have any claim to it. But his version was the one that most influenced Hendrix’s version. After Jimi became big, people in England assumed Tim Rose wrote it, because he was already known for [air quotes] “writing” “Morning Dew.” It’s just a mess.

Tim Rose’s version reaches Jimi through a woman named Linda Keith, who’s pivotal in this story.

And Chas Chandler. Linda Keith is in New York, she’s Keith Richards’ girlfriend at the time. She went first to the people in the Stones organization who she knew, like Andrew Loog Oldman, their manager at the time. For whatever reason, no one in the Stones crew was impressed [with Jimi].

Chas Chandler is in the Animals, they’re on tour, and he’s told them he’s going to quit and go into production and management. He knows Tim Rose’s version, and he loves it thinks it could be a hit if he can find someone to record it.

So Linda sneaks this info to Jimi.

Yes, and tells Chas, “You gotta see this guy, he’s playing at the Café Wha.” She then tells Jimi to learn the song. Chas goes to the show and has a revelation and wants to work with Jimi.

She also tried to get Seymour Stein interested.

I don’t know how she knew Seymour Stein, but she invited him, too. Something could’ve happened there, but as the story goes Jimi and Linda had an altercation one night, and that turned Seymour off.

Billy Roberts is a—white man? Black man?

White man. Grew up in South Carolina, in a blues environment.

I don’t think I realized that until just now. Which speaks to how much Jimi is linked to the song, and I assumed the writer was black. You then take the song to embody the archetype of the black outlaw, with both Jimi’s and Wilson Pickett’s and Lee Moses’s version.

Ice T. Black Uhuru.

I don’t really buy your Black Uhuru argument, by the way. They covered it late in their career, it wasn’t a hit, and it’s not even very good. You spend one paragraph talking about it, and yet you give them co-billing in a chapter title.

OK, yeah, true enough. It’s not the greatest version. That was more a chance to write about reggae in general.

But I thought, okay, here’s a song written by a white guy who grew up wanting to be a part of this black music tradition, and initially the song is recorded by a bunch of young white dudes. It isn’t until Jimi records it that it fulfills this promise of calling back to the black outlaws of Stagger Lee, etc. I found that endlessly fascinating. Jimi opened the door for all these other artists to interpret the song in their own way. The fact that Jimi infused it with the black experience, and coming from a broken home in the projects in Seattle, that had a lot to do with it. Alcoholic mother.

We don’t know that Joe is black.

We don’t. That’s a great point. Growing up, that’s something I never thought about, because I only knew Jimi’s version. Through my own developing conception of the world, I assumed Joe was black, and whether that’s right or wrong, I don’t know.

As to your point about not knowing Billy Roberts was black, have you seen the Sly Stone documentary?'

Of course!

In the first 10 minutes, there’s a montage of San Francisco music in the mid-’60s, all these quick cuts. There is a split second of Billy Roberts’s folk trio. I managed to screen-capture it, and that’s the only film I’ve ever seen of him that exists. It’s a total blink-and-you-miss-it thing. There’s only a handful of photos of him that I’ve found.

I found the story about the violent gentrification of the Fillmore in San Francisco fascinating.

Me too. That’s a story I didn’t know before. It’s a wild story.

It seems fishy.

Yeah. I wouldn’t go so far as to accuse Bill Graham of doing anything about it, but it was weird timing, for sure.

I have to admit that I had never listened to Patti Smith’s “Hey Joe,” because when I first became a fan, that song wasn’t easy to find. And since the dawn of streaming I had just never gone back to look it up. I only listened to it for the first time while reading this book. I had no idea that she inserted Patty Hearst into the song.

I don’t know if you remember that day you and I were at She Said Boom on Roncesvalles, but you recommended I pick up Jeffrey Toobin’s book [about Hearst], which became my primary source.

Great book! Too bad about him. But it sounds like Lenny Kaye agreed with your take on Patti’s version. What if he hadn’t?

I guess I’d have to take my lumps.

You said he did correct something?

Just the date the record was released. I thought it came out later, but he said the singles were pressed within a month.

Is the Spirit version really that good, or is it just an excuse to tell the strange story of Spirit?

Ha! I think it’s great. It’s one of my favourite versions. The more I got into the whole story of [Spirit guitarist] Randy California, man, if anyone needs a movie made about their life, it’s this guy. I talk about the Spirit version alongside Roy Buchanan’s, and I love his as well. I wanted the chapter to talk about Jimi’s influence as a guitar hero after he died, but not with the typical examples. That’s why I threw in “Maggot Brain,” too, because it’s coming from the same place as “Hey Joe.”

Clearly, as that guy in Europe can attest, you have hundreds of versions to choose from. Roy Buchanan has a fascinating story; Spirit has a fascinating story. So again: are you just using the song as an excuse to tell those?

Well, no. I focused on those as well because they had a direct connection to Jimi. Of all the artists, I wanted them to have some kind of connection.

And yet some don’t. Like Nick Cave and Charlotte Gainsbourg.

Sure, but those versions come later on, so I wouldn’t expect that.

Reading the Roy and Randy chapter, I thought, is this a cursed song? It’s also interesting that they would cover that song as opposed to “Purple Haze” or another Jimi song. Is it because it’s more of a modern standard? Does that give them a window into it, to wrestle with his legacy with a song that’s not exclusively his?

Fair point. Not sure how to answer that. It represents Jimi, and for an artist like Roy to cover “Purple Haze”—that wouldn’t make sense. Roy did his fair share of drugs, but he wasn’t a psychedelic wizard or anything. He was looking for a song to pay tribute to Jimi that was grounded in what he knew musically. Maybe the same with Randy. But Spirit often played “All Along the Watchtower,” too. “Hey Joe” is a song that is grounded in the tradition they grew up in.

The version that surprised me the most, which you don’t dwell on, is Deep Purple’s. Which I loved!

I’m surprised!

I am, too! I love that it goes many different places, often irreverent, places you don’t expect that song to go to, musically. Later on you talk about how Nick Cave gives it a bolero feel, which Deep Purple also do for one section. It seems to be the most musically expansive version I heard. Almost all the others are a garage-rock rave-up, or something derived from the Tim Rose/Jimi arrangement.

How did you come to the Charlotte Gainsbourg story?

I found interviews with her, where she said that was Lars von Trier’s conception of the movie [2013’s Nymphomaniac], was this female character named Joe and he wanted “Hey Joe” to be the theme song for the movie. I still haven’t been able to watch the whole movie (laughs). If he made a condensed version, maybe it’d be better. But the thought of a four-hour exploration of sexual deviancy…

It’s one thing when Patti does the song, because she’s trying to shoehorn Patty Hearst into it. When Charlotte Gainsbourg does it, she is, to my knowledge, the only other woman to do it—

Cher did it.

O fuck, right. That’s terrible. That’s an example of “singer sees lyrics seconds before approaching the microphone.” It’s such a flat rendering.

When I was growing up, I thought it was a misogynist song—even though it’s narrated by an innocent bystander, and I’m not sure I understood that at the time, either. I didn’t listen closely to the lyrics because the music was so powerful.

You link Gainsbourg’s version into the history of female revenge fantasies, alongside contemporaries like Tori Amos and the Dixie Chicks. That’s the flip side of male murder ballads. I don’t know if Memphis Minnie had any in her repertoire.

The one I always point to is Geeshie Wiley, “Skinny Leg Blues.” The classic line that gest me every time, “I’m going to cut your throat, baby, and look down into your face.” There are a lot of female blues singers in the ’20s who did stuff like that, but if you want to talk harrowing, that’s the one.

You even bring up the Rape of Lucretia at one point.

That was my tribute to Nick Tosches: taking it back to ancient Rome.

Finally, what is the strangest version of “Hey Joe” and is it Soft Cell’s?

Soft Cell’s is pretty strange, but the one I’ve been pointing to is one of the last versions I stumbled on. It’s by a Japanese band called the Golden Cups. They were the house band in a bar on a U.S. Army base in Japan in the late ’60s. They learned their entire repertoire from Armed Forces radio. Their version is a combination of every version up to that time.

Even Deep Purple’s?

They probably didn’t hear that one. But yeah, it’s just bonkers. It’s nuts, man.

Finally: why did you dedicate the book to the late Dallas Good?

Because I imagined he would be one of the people who would appreciate it most — and also be my toughest critic. I always learned something new whenever I was fortunate enough to talk to him about music. Even when we were supposed to be talking about the Sadies, the conversation would invariably veer off into some dark corner of country or garage rock. I hope he got a kick out of just having me be interested in all the arcane knowledge he possessed. I miss him so much.

—

Hey, you read all the way to the end! Here’s an anniversary prize: