I've got my own seeds

I've got my own weeds

I've got my own harvest

That I've sown

Anyone checked in with Rachel Dolezal recently? Just wondering.

I thought about that while listening to the news and visiting my parents on the weekend — at least, I think they’re my parents. That’s what I was told my whole life. Who knows?

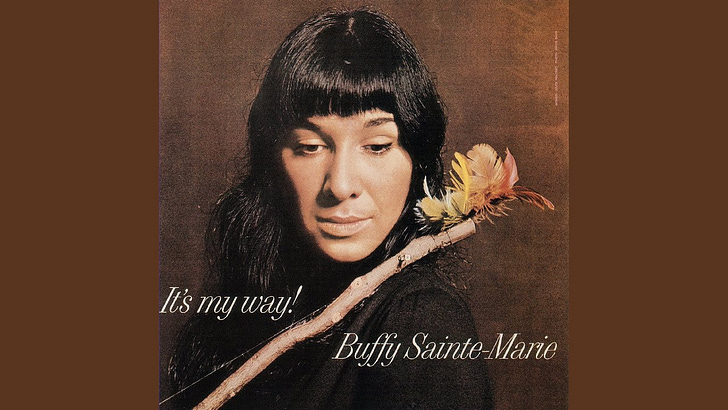

I’m a big Buffy Sainte-Marie fan. I came to her music later in my life, but then dove in deep. I’ve read both her biographies. I’ve dug through record crates to find original vinyl copies of her early records. I’ve interviewed her and seen her live several times.

Last week’s CBC bombshell was shocking. As a fan, I’m biased, but: I think that bombshell is mostly bullshit. [EDIT: The first version of this story had the word “bombshell” in the headline. That was inappropriate considering current headlines elsewhere.]

(Warning: WhiteManTM opinions ahead. From Gord Downie’s biographer, no less, who wrestled with the Joseph Boyden issue in a chapter of The Never-Ending Present.)

Buffy won an Oscar for her songwriting, in 1983. But if everything in the Fifth Estate documentary is true, then she should get an honorary Oscar for being the greatest actor of all time. Talk about method acting!

Sure, it’s quite possible that we’re talking about someone not necessarily fraudulent but capable of fabulist delusion that seems beyond human capability.

But I seriously doubt it. For starters, that would take a shitload of effort to walk the walk every single hour of every day, which, by any account I’ve ever read, is what Buffy Sainte-Marie does.

I think there’s a lot of context missing. Especially for people who only know the bullet points of her biography. People who write things on Facebook like, “I've never felt that Buffy Saint Marie looked authentically brown. She looks tanned, like from a tanning bed.” (That’s a real comment, spotted on a friend’s page.) People who think that Buffy might have claimed to grow up on a reservation or an Indigenous community.

The 82-year-old never did claim that. She has always said that she grew up in Massachusetts with a white family and that she herself had many questions about her own roots. Decades ago, that was a story people easily bought. Now it raises red flags for those who want to out “pretendians.”

The documentary cherry-picks different statements Buffy made over the years that suggest her story’s details changed. Some could easily have been misquotes or misprints; it’s not like the mainstream media were sensitive to details in Indigenous culture at the time (or, sadly, now). I wouldn’t trust a cub reporter from 1965 to know the difference between Cree and Algonquin.

A few statements are fishier than others, in their inconsistency. But part of me wonders how consistent anyone would be when constantly retelling their life story for 60 years.

Buffy released her response to the allegations here, and followed it up with a video statement here. Read/watch those before you listen to anything I have to say.

Buffy’s art and her activism speaks for itself. Both are exceptional. She didn’t win an Oscar because she was Indigenous. “Universal Soldier” didn’t become a 20th-century folk standard because she was Indigenous. Elvis Presley and Barbra Streisand didn’t cover her songs because she was Indigenous. She has been nothing but a positive force for good, including her groundbreaking work on Sesame Street — though that’s a gig she definitely did get because she was Indigenous. And where generations of Indigenous people will tell you she did very important work.

She didn’t defraud anyone — except perhaps Canadian arts and government institutions eager to applaud someone who, if she was born in Canada at all (an assertion that is now definitely debatable), left the country as an infant.

That’s not an Indigenous issue, and it’s not unique to Buffy: ask yourself why Eleanor Catton is on the Giller shortlist this year, or why Astra Taylor is this year’s Massey lecturer. No disrespect to either woman, but both left Canada as small children. That’s an argument that’s been going on as long as Neil Young’s been winning Junos.

But that issue is the opposite of political dynamite, which Buffy’s story definitely is.

Buffy didn’t swindle anyone out of money or opportunity — quite the opposite (we’ll talk about the Junos, though, in a bit).

She identified herself as being Indigenous at a time when it was not remotely a commercially lucrative stance to take. There were no other Indigenous singers anywhere near the spotlight then. (Go ahead — name one. From 1964.) There were only one or two Indigenous actors of any note. No one in the dominant culture was interested in Indigenous stories, at least not ones told by Indigenous people themselves. Sure, some hippies and academics and the occasional TV interviewer were curious, but if young Beverly Sainte-Marie (Santamaria) wanted to be a star she’d have a much easier path as a white woman like Joni Mitchell or Joan Baez.

She chose the path of most resistance. That’s not something an opportunist does.

If it’s being suggested that she extracted cultural capital from Indigenous communities, it can be successfully argued that she paid it back a thousandfold. What Harry Belafonte was to the African-American civil rights movement — a financial benefactor and vocal supporter in ways that were politically unpopular — Buffy was to the American Indian Movement. For years when she was in the commercial wilderness — because it was still not remotely lucrative to be an Indigenous performer — she toured reserves in out-of-the-way locations that no other professional musician would ever dare to go. Is that opportunism?!

A friend who is an Indigenous studies professor wrote this week, “[Buffy] is someone who has been Indigenous when it was dangerous to be Indigenous, when her songs were banned from radio and there was no financial gain from it. She has given more to Indigenous people than perhaps any artist I know of.”

Drew Hayden Taylor, who made a feature-length doc about the “pretendian” trend, wrote about this complexity in the Globe this week: “It would take at least a dozen or more brilliant Indigenous artists combined to make it halfway up Mt. Buffy.”

To state the incredibly obvious, Indigenous ancestry can be complicated for myriad reasons. Family secrets are hard (ask Tom Wilson, who had the reverse experience of Buffy’s). They’re exponentially harder for adoptees — or, as might be the case with Buffy, and as she alluded to in her public statement (“born on the wrong side of the blanket”), even harder still for children born out of wedlock. And if that’s the case, then no wonder her birth family is confused and hurt — and it’s none of our business.

The Fifth Estate documentary doesn’t even get into that possibility — it does, however, talk to that one cousin who met her once, and the niece whose father was accused of sexual abuse, allegations that cast doubts on motives here, both Buffy’s and her brother’s.

The doc sides with the brother.

Family secrets are hard.

They’re even harder when there is estrangement involved — that’s a whole other issue, one I won’t get into here. But it’s one that should be — and is not — being factored into the broader discussion by those quick to condemn.

The documentary produces Buffy’s birth certificate, in Massachusetts, listing both parents as “white” — which was something American birth certificates did at the time, because of course they did, decades before the civil rights movement.

But what does that birth certificate mean?

Buffy has always said her mother was part-Mi’kmaq from Nova Scotia. That may or not be true, and there’s no one alive to back it up. Would it be so weird for a (part-) Indigenous woman married to an Italian man to self-identify as “white” in a suburban Massachusetts town? Or maybe her husband filled out that form? The doc just accepts it as truth.

Millions of “white” North American families (including my own) have that one Indigenous relative from more than a century ago. Buffy’s mother may or may not have had relations with Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia; maybe it was a distant relation of family mythology, or maybe it was more direct.

Then there’s the “born on the other side of the blanket” theory: documentation shows that Buffy was born to her mother in that Massachusetts hospital. Family pictures suggest there is a resemblance with her siblings. But who’s to say that Arthur Santamaria was her father? (The family anglicized — or gallicized — their Italian name; that wasn’t Buffy’s doing.)

Is it not possible — reading between the lines of Buffy’s video statement this week — that Winnie Santamaria, part-Mikmaq, had an affair with a Cree man from Saskatechewan, resulting in a story she may have told her child?

And if so, what child does not believe their mother?

Or: if Buffy was born out of wedlock, maybe Winnie made up a story about the biological father’s history, to make it seem unlikely that Buffy would ever find him? I mean, what are the chances young Buffy from the Boston area would ever go to Saskatchewan to look for him? Who goes to Saskatchewan?!

Is any of this any of our fucking business? Yet here we are.

One of the Indigenous academics in the doc says the fact that Buffy claims both Mi’kmaq and Cree ancestry doesn’t make sense. But why not? Has there never been a child, Indigenous or otherwise, born to parents from either side of the country?

The town clerk interviewed by the CBC points out that the birth certificate is numbered and appears sequentially beside “live births” registered the same week by the same doctor. This is offered to counter the idea that Buffy was adopted in Saskatchewan and then registered later in Massachusetts.

Documentation around Indigenous adoption is notoriously shady. In the acclaimed new APTN series Little Bird, about a Sixties Scoop survivor (with a theme song by, yes, Buffy Sainte-Marie), the protagonist finds her birth certificate registering her birth in Montreal, and yet also finds an ad in a Saskatchewan newspaper with her picture and the tagline “Adopt me.” The Montreal birth certificate was obviously forged after the adoption.

I realize I’m citing a fictional example, but reading about what research and sensitivity went into the creation of Little Bird, I’m going to have to assume that incidents like this were not unheard of.

The documentary quotes the Saskatchewan government refuting the notion that its own record-keeping might be shoddy. Do you believe the Saskatchewan civil service?

In her 20s, at a powwow on Manitoulin Island, Buffy met a chief from the Piapot First Nation in Saskatchewan. That is where from she was led to believe, via Winnie Sainte-Marie, she might hail. The chief and his wife soon adopted Buffy directly into their family — not with an honorary tribal affiliation, like, say, Gord Downie’s gifted Lakota spirit name, Wicapi Omani — but as a family member, as one of their children.

In the family’s own statement this week, they affirmed that Buffy is very much a part of their family, personally known and beloved to generations there. It’s not a cosmetic affiliation. She goes there often. She’s put in the work. Challenging that concept of a chosen family is, in many ways, an affront to adoptees and adopted families everywhere.

Let’s assume for a minute that Buffy Sainte-Marie is a massive fraud, capable of pulling off one of the greatest deceptions in the last 100 years of North American culture.

What harm did she cause?

This is where the tall poppies come out to play.

“She took opportunities that could have gone to other Indigenous artists!”

I’ll buy this argument if you can tell me what kind of opportunties were available for Indigenous artists 60 years ago — or any time before the relatively recent, post-TRC reckoning and wave of WhiteGuiltTM. Or if there’s an Indigenous songwriter of similar talent in her era — such is Buffy’s stature that finding a worthy challenger is like trying to find the second-best band in Liverpool in 1962 and why they should be bigger than the Beatles.

From whom did Buffy steal opportunities? She created opportunities.

“She got grant money that should have gone to Indigenous artists!”

Ah yes, grant money. The biggest bugaboo of every Canadian artist with a grievance to air, and the shortest path to petty jealousy.

Buffy Sainte-Marie’s entire career was in the United States: American record labels, American management, etc. She definitely did not build her career on Canadian grant money. She started her career when the few grants that did exist only went to symphonies and ballet companies.

I do notice that 2015’s Power in the Blood — an album she made with Canadian producers and musicians and released on a Canadian label (True North) — does have logos for Canadian and Ontario funding agencies on it. That might just have to do with the label’s annual operational funding, not her album. (I’ve never received a dime of grant money, but those logos appear in my books because my publisher gets that money.)

Does Buffy Sainte-Marie apply for and get Canadian grants? If so, I would have a problem with that — but that’s because she lives in Hawaii, not whether or not she’s Indigenous.

“She won awards in Indigenous categories that should have gone to Indigenous artists!”

This one is a bit sticky.

Buffy Sainte-Marie is partially credited for the creation of an Indigenous category at the Juno Awards in 1994. The idea began with broadcaster Elaine Bomberry, and her friend Shingoose, who then enlisted Buffy’s help and whose clout helped it come to be. Andrea Warner — who is also the author of Buffy’s 2018 authorized biography — wrote a good history of the category for CBC Music here. Read that and try and tell me Buffy is some kind of ladder-climbing opportunist. Any door she walked through, she held it open for others.

HOWEVER. I do have a huge problem with Buffy, having helped create the category, not recusing herself from being nominated in it.

She’s won four Junos in that category since 1997. Again — regardless of Indigeneity — this smells bad to me. Imgaine if Margaret Atwood created a new literary award and then won it several times over? By 1997 Buffy was already an icon and didn’t need any Juno awards in a marginalized category — she was a Hall of Fame inductee in 1995.

Either way: I’m not convinced that a Juno win in any of the smaller categories is any kind of major career boost — mostly because so few people care or even notice. (I barely do, and it’s my job.) If you were nominated in the same category as Buffy Sainte-Marie, I’m not sure an actual win would have done you any more favours — and really, being in the same category as Buffy Sainte-Marie might be the biggest favour you could get at the Junos, to be considered at the same level of artistry as a legend.

That’s the Junos, which is run by white people. Buffy also won awards from Indigenous arts associations — that’s their business, and not my place to comment. Some people who believe the allegations (including a group that doesn’t seem to exist other than on social media) are calling for those awards to be rescinded.

I’ve also seen calls to have her honorary doctorates revoked, which is downright dumb. Those were for her actual achievements, not her bloodline. Unless… they were. Nobody likes to tick off boxes more than academics do.

There’s too much more to say. About the fetishization of authenticity. About how much we all — but especially those in the public eye — construct identities, and to various degrees. About what Nancy Leong calls “identity capitalism.” About stories our family told us and what we believe or don’t (ask Sarah Polley). About our need for heroes, and about how they are inevitably flawed because they’re human. About how when our heroes seem too good to be true, we’ll find ways to knock them down, deserved or not. About how often there’s only room for “the one” from a marginalized community to be accepted by the dominant culture, and on what terms.

Even if all these allegations are false, this has been an incredibly damaging week. Indigenous people will never look at a hero the same way. Everyone else will be even more cynical than we all already are. There will from now on always be an asterisk beside Buffy’s name. Racists will have a field day on how white guilt has obviously made it so lucrative to be an Indigenous person that a woman like Buffy would fake her way through a lifetime charade. Hell, Canada’s left might even join the right with calls to defund the CBC!

This story is way more complicated than a 45-minute Fifth Estate documentary chooses to explore. But now it’s a sound bite. And Buffy loses. So does, I would argue, an important artistic and cultural legacy.

I was, and remain, a fan of Buffy Sainte-Marie. No matter how this shakes down. Leave the grandma alone.

From her very first album:

I've got my own stakes

In my own game

I've got my own name

And it's my way

I've got my own kith

I've got my own kin

I've got my own sin

And it's my way

I've got my own peace

I've got my own wrath

I've got my own path that only I can go

I've got my own sword in my own hand

I've got my own plan that only I can know

Buffy's story changes ove the years. For many years, Buffy claimed she was born in Saskatchewan, which contradicts her current story that she doesn't know where she was born. Buffy claims her mother told her she was adopted, a story that her birth family has no knowledge of. Buffy claims her mother had Micmac blood, another story her birth family has no knowledge of.

Your assertion that Buffy's birth certificate from 1940s Massachusetts could be fabricated is justified by assertions that this happened in some adoptions in Canada in the 1960s (talk about a stretch).

Buffy's assertion that she was indigenous began when she was in her 20s in the Greenwich village folk scene in NYC. I can imagine this began more as a lark than anything else. Lots of young folk coming to the Big City create a new identity. Over the years, this story could have taken on a life of its own and may have opened some doors - how else did she end up being invited to a powwow on Manitoulin Island?

This claim of being indigenous seems to have become foundational with her gig on Sesame Street in the 1970s. This was when she threatened to claim her older brother had sexually abused her if he persisted in claiming he was her brother and that she was not indigenous.

People are complicated and Buffy has definitely had a career that inspired many indigenous people. I'm not sure she really qualifies as a Canadian indigenous artist despite her native adoption. It is possible to be adpted and not be indigenous at the same time.