The Globe and Mail published a list of “101 Canadian Albums You Need To Hear” over the weekend. It’s—a list. Lots of obviously great choices, plenty of pleasantly revisionist surprises, no shortage of omissions. What is a list, except something to argue about? I contributed a ballot, but not any blurbs. More on that much further below.

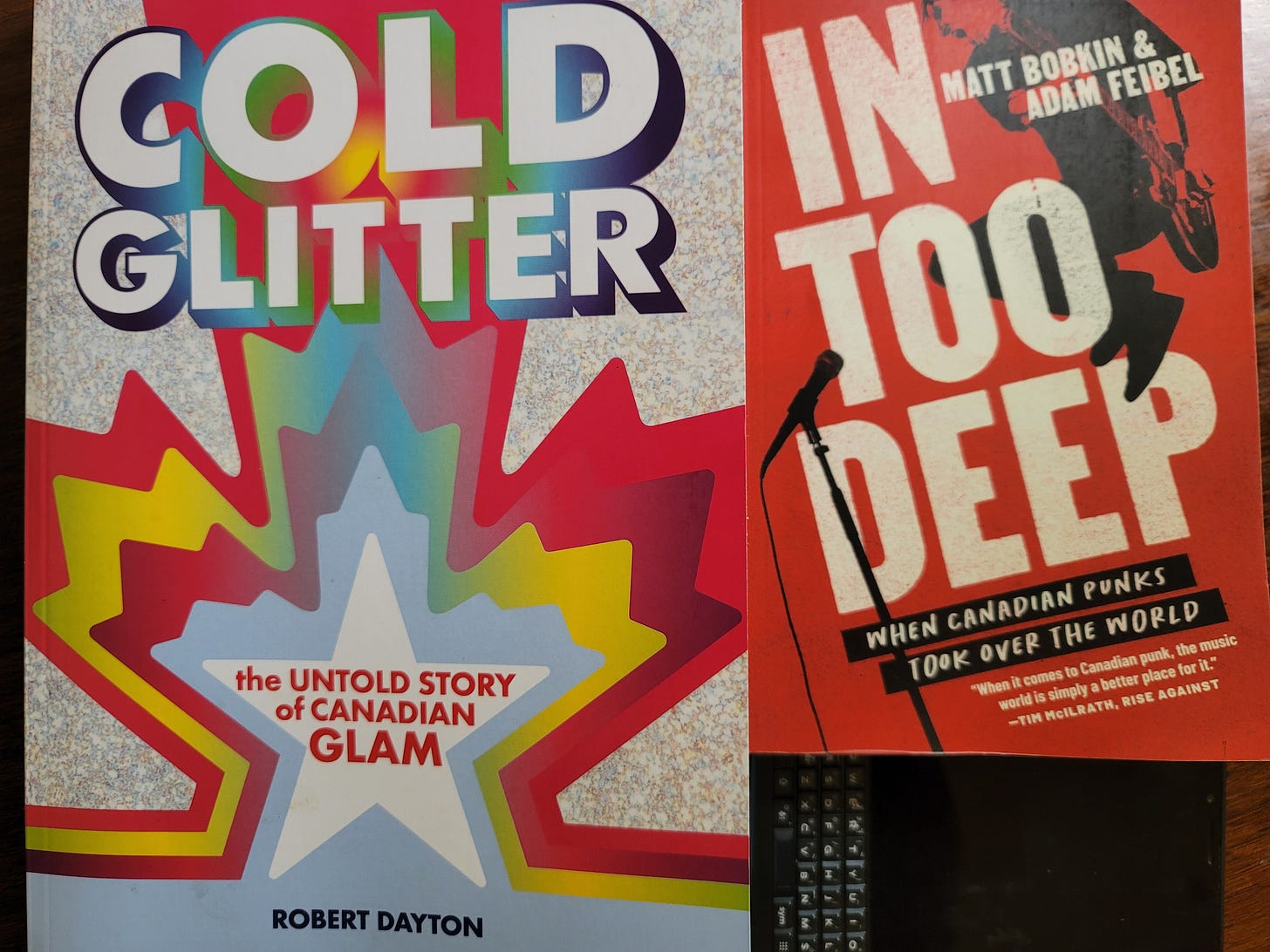

There are two excellent new Canadian music books on the market this month: Robert Dayton’s Cold Glitter: The Untold Story of Canadian Glam, and In Too Deep: When Canadian Punks Took Over the World, by Matt Bobkin and Adam Feibel. Rare is the year when two such books appear; rarer still is a month when that happens.

Only one album from each book is on the Globe’s list (Rough Trade, Avril Lavigne). This is not critically accepted Canadian musical history, even if the artists in the pop-punk book sold hundreds of thousands of records and tickets, often millions.

—

If you’re new here: I write books. (I also edit them; contact me if I can help you.)

Growing up as a young Canuckophile, I was thirsty for Canadian musical history. There was very little, almost nothing, to read on the subject. By 2001, when Have Not Been the Same was published, there was a little bit more, some of it even readable! (Shout out to Nicholas Jennings and Dave Bidini, whose late ’90s books were a breath of fresh air and a huge inspiration.)

I can’t speak for my two co-authors on HNBTS, Jason Schneider and Ian A.D. Jack, but I know I didn’t have any grand commercial hopes for the book: I just wanted it to exist, to be a document of my generation’s Canadian music (which was roughly 1985-95). Further, I wanted it to inspire others, even if it was because they thought we failed and they could do better.

Since 2001, I’m incredibly grateful to learn that Have Not Been the Same has been influential, cited by academics and other writers (including Charlie Angus, who quotes from it in his recent memoir Dangerous Memories). And it exceeded my low Gen-X commercial expectations: the initial run sold out and warranted a 2011 revised edition, which is still in print and has a long tail of (very modest) sales to this day.

(I wish more people had read Schneider’s prequel, Whispering Pines, or read my sequel, Hearts on Fire, but whaddyagonnado.)

But enough about me. On to these books.

In Too Deep, by Matt Bobkin and Adam Feibel

(House of Anansi)

In Too Deep is about music that is critically reviled: Sum 41, Avril Lavigne, Billy Talent, Simple Plan, etc., music that teenagers loved but that Gen-X and Boomer rock critics thought was juvenile and easily dismissed. Ironic, of course, because what was rock music originally—and punk in particular—but a generational divide?

In Too Deep’s authors both wrote for Exclaim! (where I also got my start decades earlier), and going through the archives they realized how the music that inspired them as youth was belittled at the time, and unlikely to be taken seriously by any other critics—except themselves.

So while I, a 53-year-old music critic, am technically the enemy here, I love the fact this book exists because of the same urgency my Have Not Been the Same co-authors and I felt to justify our generational taste. I was more than happy to read about music that I mostly hate.

I learned a lot, like how both Avril Lavigne and Fefe Dobson pushed back against record company’s attempts to make them pure pop. I learned about just how massively popular Silverstein was, even while being a punching bag for haters both inside and outside their scene. The origins and evolution of Simple Plan are more interesting than I anticipated. And the fact that the father of Josh Ramsay of Mariana’s Trench founded fabled Vancouver studio Little Mountain Sound, and that Ramsay’s favourite band is Jellyfish, explains so much. (It’s also interesting that Ramsay’s role in “Call Me Maybe” is treated as a minor footnote.)

Because Billy Talent and Alexisonfire are both characters in my book Hearts on Fire, their stories here were less revelatory for me—and, sadly, less juicy. Because I am a writer and therefore inherently petty and competitive, I’ll argue that my book has funnier and wilder stories about both bands.

That’s my sole complaint about In Too Deep: if the writers’ intention was to legitimize much-maligned music, I feel they erred a bit too much in writing conservatively. There’s a bit too much about chart metrics, and song placement in forgettable movies. Something in the approach here is a bit too… Canadian? It’s like if Billy Talent wrote a ballad called “Try Earnesty.”

It’s not a dry read, not at all, far from it. It certainly never lags, it reads like butter and both men are very good writers—but I feel like this book should be more fun.

(That said, I feel the same way about the tone of Have Not Been the Same; takes one to know one.)

The authors were thrown a huge challenge when, mid-way through writing, Deryck Whibley of Sum 41 dropped bombshell allegations against Treble Charger’s Greg Noiri, accusing him of sexual assault, grooming and fraud. In the tiny world of the Canadian music industry, this was huge. Whibley writes about it extensively in his 2024 memoir, Walking Disaster (which is well worth reading for myriad reasons other than scandal, reviewed it here).

Bobkin and Feibel, on the other hand, mention the accusations only in a footnote. I understand why they’d do that, legally, as Whibley and Noiri are suing and countersuing each other as we speak. Also, getting into the details would also be a huge tangent in a narrative that focuses exclusively on the music and the business. That exclusion wouldn’t fly if they were talking about Hedley, but with Whibley as the victim it’s a different story—and a story Whibley himself tells in his own book. (He didn’t grant an interview for In Too Deep, though his bandmates did.)

Most important: In Too Deep fills a neglected historical gap. It rightfully rails against the punk police who wanted to test a teenaged Avril Lavigne’s knowledge of the Ramones. It celebrates Canadian ambition (imagine that!), and artists who bend the industry to their own ends. There are lessons here for musicians of all genres. It captures a particular time in both the history of punk music and a transformative time for the music industry in general.

And it does not care if you think it “sold out,” whatever that may have once meant.

Cold Glitter, by Robert Dayton

(Feral Press)

Cold Glitter is an instant classic of weird Canadian history. It’s also laugh-out-loud funny, on almost every page. It’s a book I never imagined existing, nor one that I thought I might need. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

It’s incredibly niche. Almost none of these artists had hit records, other than Sweeney Todd (“Roxy Roller”) and Rough Trade. Some had international cult audiences, like the bodybuilder carny act that was Thor. Some had minor regional hits, or became favourites in the anything-goes days of CFNY. Some never even put out a record.

Some went on to respectable careers, like Flivva guitarist Michael Brook (Mary Margaret O’Hara, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan), or the teenaged members of Calgary’s Buick McKane, who became Shadowy Men on a Shadowy Planet.

What, exactly, is glam music? There’s no musical definition: it could be hard rock, disco, cabaret, prog weirdness, or pretty much any other pop/rock genre between roughly 1970-82, between T. Rex and the New Romantics of new-wave pop. (Though I’d argue it extends into hair metal up to 1990.)

Author Robert Dayton doesn’t care to be defined: for him, glam simply refers to any musicians with a flair for the flamboyant and flashpot mishaps on stage.

Mostly, it’s a reason to celebrate musicians who had very un-Canadian ambitions to simply be fabulous and larger than life. The more ridiculous they now look to contemporary audiences, the better. Dayton himself doesn’t see them as ridiculous, though he’s aware that most will.

Dayton himself is a musician (Canned Hamm, July 4 Toilet), comedian and artist. He’s also a massive nerd who writes with exuberance and exclamation points that never seem superfluous. He’s a born performer; this would make a great audiobook. He has massive respect for the audacity of these artists, who dared to dress like space aliens while playing week-long residencies in North Battleford, Saskatchewan, or whatever, wherever. He likely sees them as kindred spirits.

I’m only halfway through this opus—best consumed in small doses, because of the embarrassment of riches within—but I wanted to file this review for Canada Day. I suspect that the stories about these artists are infinitely better than their actual music—though does that matter when this is such a good read? I could cite numerous stories and anecdotes to convince you to read this book, but it’s better to be surprised. (I will say that his encounter with Bryan Adams about the superstar’s time in Sweeney Todd is pretty great.)

Cold Glitter is a dagger in the heart of beige Canadiana, celebrating the fact that the closer you look, the weirder this country gets—for the better.

Now, for paid subscribers, about that Globe list and my ballot:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to That Night in Toronto to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.